August 28, 2021

Have you ever been scrolling on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok and watched a video of a monkey, ape, or lemur? Maybe they’re wearing a dress, holding their arms up being “tickled”, or being held by someone posing for a photo. These videos can be tempting to share with your friends and family. So much content on social media is centered on animals interacting with the world and people, sharing it seems like a harmless way to bring positivity to someone’s feed. Unfortunately, the truth behind many of these videos is that it fuels the live primate pet trade, threatens wild populations, promotes poor primate welfare, and distorts viewers perspectives on zoos and the differences between private ownership of primates and housing primate species in zoos to support and assist in wild conservation efforts.So, what is the live primate pet trade? The primate pet trade is the transaction of live primates (monkeys, ape, and prosimians) into the care of humans outside of accredited zoos or sanctuaries (Norconk et al., 2019). Some of these primates will have come from facilities that intentionally breed them for the purpose of selling them as a pet, while others will have been taken directly from the wild by traffickers and then sold (Norconk et al., 2019). These primates will all be taken from their mothers and sold at young ages before they have reached full growth and maturity (Noconk et al., 2019).

It was estimated in 2011 that around tens to potentially hundreds of thousands of wild individual live primates are traded a year; in 2017 the number was estimated to be around 450,000 live primates (Nijman et al., 2011; Estrada et al., 2017). In 2011, the United States was the single largest importer of live primates and had been since 2009 (Nijman et al., 2011; Norconk et al., 2019). It goes without saying that these numbers present a major concern for primate populations and their conservation.

Primates are imperative to the health of the ecosystems they inhabit. With continually decreasing population numbers, and approximately 60% of primate species threatened with extinction, primates will no longer be able to support the functions necessary for an ecosystem to thrive (Estrada et al., 2017). Primates are responsible for a significant amount of seed dispersal and pollination throughout forests (Estrada et al., 2017). Since many primates are frugivorous (eat fruits), they are able to disperse fruit seeds throughout long distances when travelling, assisting in forest regeneration (Chapman et al., 2013). In addition to forest regeneration, primates disperse seeds that grow plants connected to economic growth, cultural importance, and food security in communities within primate habitats (Estrada et al., 2017).While the impacts removing primates from the wild has on ecosystems and local peoples will have a multitude of consequences, it is important to discuss how the live primate pet trade impacts the individual’s health and welfare once in the hands of its “owner”. The majority of primate species are social animals and require the presence of conspecifics to engage in natural behaviors such as grooming, playing, breeding, and various other species-specific behaviors. When taken out of these social environments and placed within human care (non-zoo or sanctuary) in an inappropriate environment such as a house, the individuals may begin to develop stereotypic or abnormal behaviors. Stereotypic behaviors are defined as “repetitive behaviors caused by central nervous system dysfunction, frustration, or repeated attempts to cope” (Mason et al., 2007). These behaviors can be functionless movements (pacing, bouncing, excessive somersaulting), over grooming oneself, or forms of self-harm that may include picking or biting at their skin forming a wound (Coleman & Maier, 2010; Lutz, 2014).

Keeping primates as pets in general, as well as in an inappropriate environment with no social groups, will have detrimental effects on the primate’s mental and physical welfare. Many primates who were previously kept as pets face lifelong struggles with harmful stereotypic behaviors and may have trouble fitting in with other primates since they were never able to learn how to be a primate when living alone as a pet. Unlike what most videos or pictures of pet primates will show, primates are incredibly dangerous animals and pose a serious risk to humans once they reach full growth and maturity. Below is a picture of Seneca Park Zoo’s dominant male Olive Baboon, Mansino, showing off his canines.Social media is becoming an increasing threat to primate populations worldwide, with certain species being more popular and appealing to viewers. As of 2020, YouTube had two billion users throughout the world, making it the most popular and impactful social media platform to exist (Moloney et al., 2021). With this many users, and the ability to share YouTube content on other social media platforms, these videos promote the popularity of having a primate as a pet and thus increases the demand for the trade of live primates and decreasing their numbers in the wild.

While there have been numerous action plans implemented to combat this issue that involve local peoples within primate habitat countries, there are a variety of ways that our visitors here at Seneca Park Zoo can help decrease the number of primates imported into the United States for pets and entertainment.

Tips for sharing videos or pictures of primates on social media:

- Was the video or picture posted by an accredited zoo? If yes, it is ok to share it! The primate is in an appropriate environment and social group and is being taken care of by professionals.

- Is the primate sitting on someone’s shoulder wearing clothes or doing tasks throughout the house? If yes, do not share it! This is most likely a primate being kept as a pet. The primate is in an inappropriate environment behaving in a way it wouldn’t normally behave in a social group in the wild or at a zoo.

- Is the primate in the wild? If yes, it is ok to share it! Sharing videos or pictures of primates in the wild is encouraged, as it shows people what primate social groups look like as well as the type of habitats the species lives in.

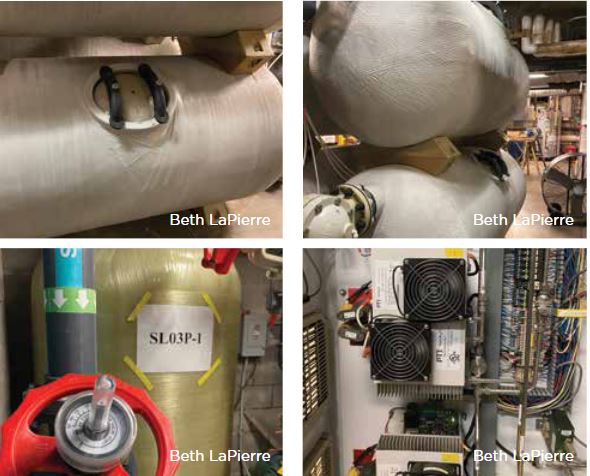

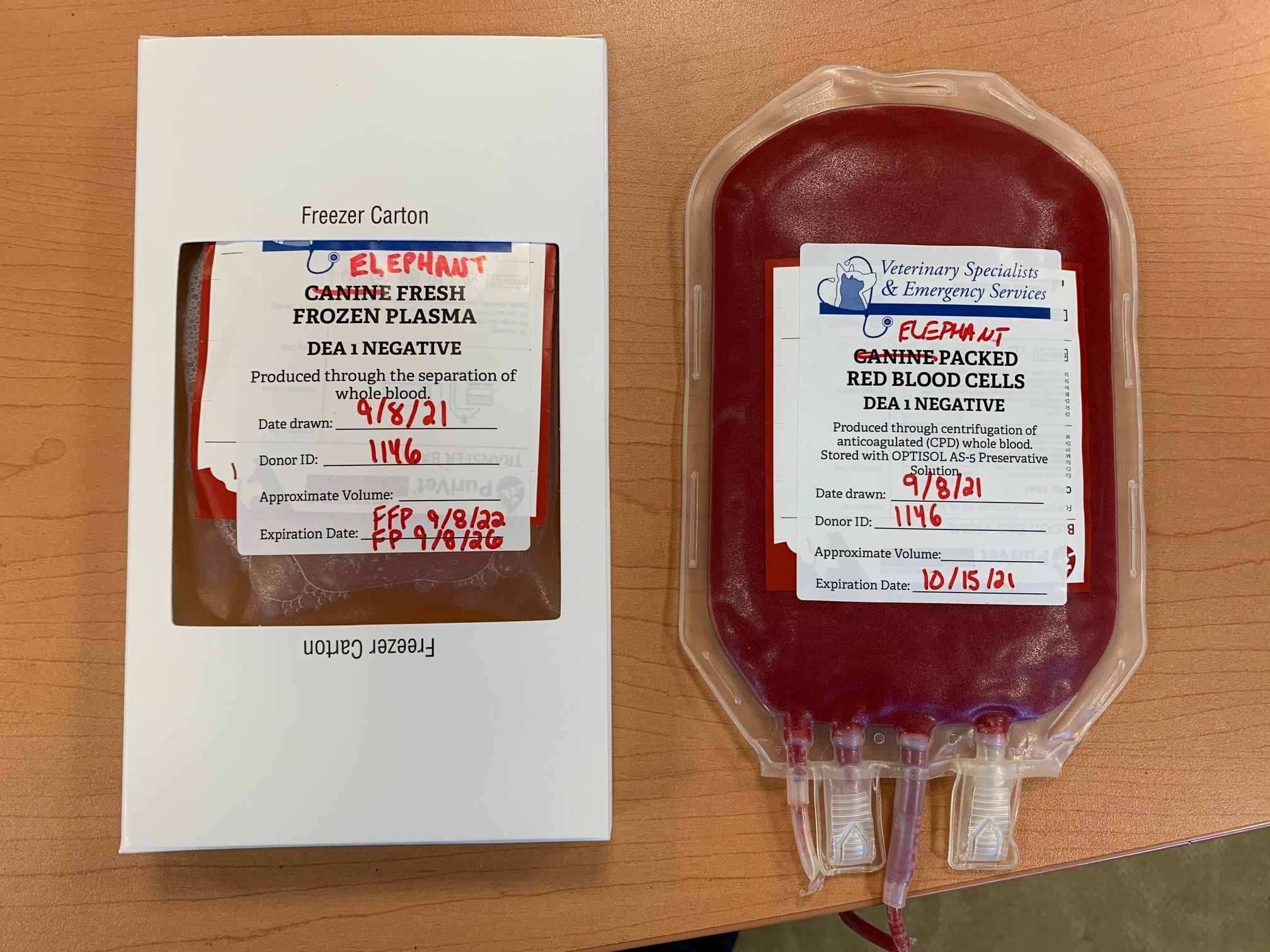

There may be some videos or images that could cause confusion when deciding if it should be shared or not. These videos or images may show a veterinarian or wildlife researcher in close contact with a primate. If these videos or images are connected to a zoo or a research/conservation group, then it is ok to share them. Veterinarians will have to be in close contact with a primate for exams or if an injury occurs. Wildlife researchers may have to be in close contact in order to collect samples (blood, fecal, urine, etc.) or even fit the primate with a GPS collar to assist in their research. Below are some examples:You may also come across videos or pictures of young primates (mainly orangutans and chimps) being held by care takers or wheeled around in wheelbarrows. The majority of these videos or pictures are taken at primate rehabilitation centers. As long as these videos or pictures are coming from a center, it is ok to share it! These centers rehabilitate primates that have lost their mothers due mainly from forest destruction and the pet trade. Sharing this content can help raise awareness about the dangers primates face in the wild and the work that is put into rehabilitating the primates and eventually re-releasing them into the wild. Below are examples:One last action our guests can take is to educate your friends and family about the primate pet trade! Sharing this information is perhaps one of the most important ways to help primates. Help us at Seneca Park Zoo spread awareness about the threat the primate pet trade poses to primate conservation and primate welfare.

Thank you for your support and Happy Primate Weekend!

– Clare Belden, Baboon KeeperDonate References:

Estrada, A., Garber, P.A., Rylands, A.B., Roos, C., Fernandez-Duque, E., Di Fiore, A., Nekaris, K.A.I., Nijman, V., Heymann, E.W., Lamber, J.E., Rovero, F., Barelli, C., Setchell, J.M., Gillespie, T.R., Mittermeier, R.A., Arregoitia, L.V., de Guinea, M., Gouveia, S., Dobrovolski, R., Shanee, S., Shanee, N., Boyle, S.A., Fuentes, A., MacKinnon, K.C., Amato, K.R., Meyer, A.L.S., Wich, S., Sussman, R.W., Pan, R., Kone, I., Li, B. (2017). Impending extinction crisis of the world’s primates: Why primates matter. Science Advances, 3: e1600946

Chapman, C.A., Bonnell, T.R., Gogarten, J.F., Lambert, J.E., Omeja, P.A., Twinomugisha, D., Wasserman, M.D., Rothman, J.M. (2013). Are primates ecosystem engineers? International Journal of Primatology, 34:1-14

Coleman, K., Maier, A. (2010). The use of positive reinforcement training to reduce stereotypic behavior in rhesus macaques. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 124(3-4): 142-148

Lutz, C.K. (2014). Stereotypic behavior in nonhuman primates as a model for the human condition. Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Journal, 55(2)

Mason, G., Clubb, R., Latham, N., Vickery, S. (2007). Why and how should we use environmental enrichment to tackle stereotypic behaviour? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 102:163-188

Moloney, G.K., Tuke, J., Dal Grande, E., Nielsen, T., Chaber, AL. (2021). Is YouTube promoting the exotic pet trade? Analysis of the global perception of popular YouTube videos featuring threatened exotic animals. PLoS ONE, 16(4): e0235451

Nijman, V., Nekaris, K.A.I., Donati, G., Bruford, M., Fa, J. (2011). Primate Conservation: measuring and mitigating trade in primates. Endangered Species Research, 13: 159-161

Norconk, M.A., Atsalis, S., Tully, G., Santillan, A.M., Waters, S., Knott, C.D., Ross, S.R., Shanee, S. (2019). Reducing the primate pet trade: Actions for primatologists. International Journal of Primatology, 82: e23079