Lake sturgeon photo by Julia Schlenker

If you ever watched “The Zoo” on Animal Planet, you undoubtedly were introduced to Jim Breheny, Director of the Bronx Zoo. Jim, a former chair of the board of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums (AZA), heads a fantastic organization known for its outstanding animal care, guest experiences, and conservation work. At one of the first conferences I attended in the Zoo world, Jim took the microphone, and said, “We can have great guest programs, and the best in animal care, but at the end of the day, why’s the monkey in a cage?”

This question gets to the heart of why zoos exist: to connect people to the animals in our care in a way that inspires them to act on behalf of these species, and the planet. The animals here serve a higher purpose: they are ambassadors for their counterparts in nature, species that we simply MUST all care about enough to take action to ensure their long-term survival.

Zoos and aquariums accredited by AZA are required to create and implement a Conservation Action Plan, which essentially is the strategic framework for how the institution accomplishes their mission. At Seneca Park Zoo, the Conservation Action Plan is updated annually, with five-year goals and annual objectives. While many of us on the “inside” are aware of the Conservation Action Plan and how it informs our work, we don’t often report out on it, to you, our members.

The entire plan is a very detailed, dense, document so the outline below gives you an overview of the pillars of the plan, and how we work to enact it.

Pillar One: Become known as a conservation organization

The Zoo’s vision is to be a national leader in education and conservation action for species survival, and we are. Yet, not a single week goes by when we don’t hear the words, “I didn’t know the Zoo did that” in reference to our conservation work. Many people still know us primarily for being a great place to visit with family and friends and remain unaware that the Zoo is a conservation organization.

The Zoo’s vision is to be a national leader in education and conservation action for species survival, and we are.

We work to ensure every touch point with the Zoo reminds you we not only care about the animals here at the Zoo, but we are committed to conservation in our community, regionally, and internationally.

Our guest surveys indicate we’re on the right track, with 95% of guests reporting they are aware the Zoo is a conservation organization, aware we are working actively to save animals from extinction, and aware we are working to restore native habitat. We want every guest, to feel hopeful and to have learned something they can do to help save animals from extinction. This year, you’ll see more conservation awareness activities at special event fundraisers like Birds, Beers, and Brews, Sustainable Table dinners, and more.

Pillar Two: Be a role model for sustainability

In essence, walk the walk, and not just talk. We teach sustainability to our guests, and we want to model that behavior in every way we can. We work to eliminate single use plastics, to recycle and compost, and conserve water. You’ll find reusable plates and utensils at Trailside Café, and water in aluminum, not plastic, bottles. These are small, but important, acts of sustainability.

This year, we will be taking a closer look at what it would take to become a zero-waste to landfill organization. We have some special constraints, but the first step in 2023 is to identify barriers and begin to build strategy to remove those barriers where we are able.

Pillar Three: Protect species through conservation research and action

This pillar speaks to a large set of activities across the entire Zoo aimed at our own efforts to save animals from extinction, as well as empowering others to act.

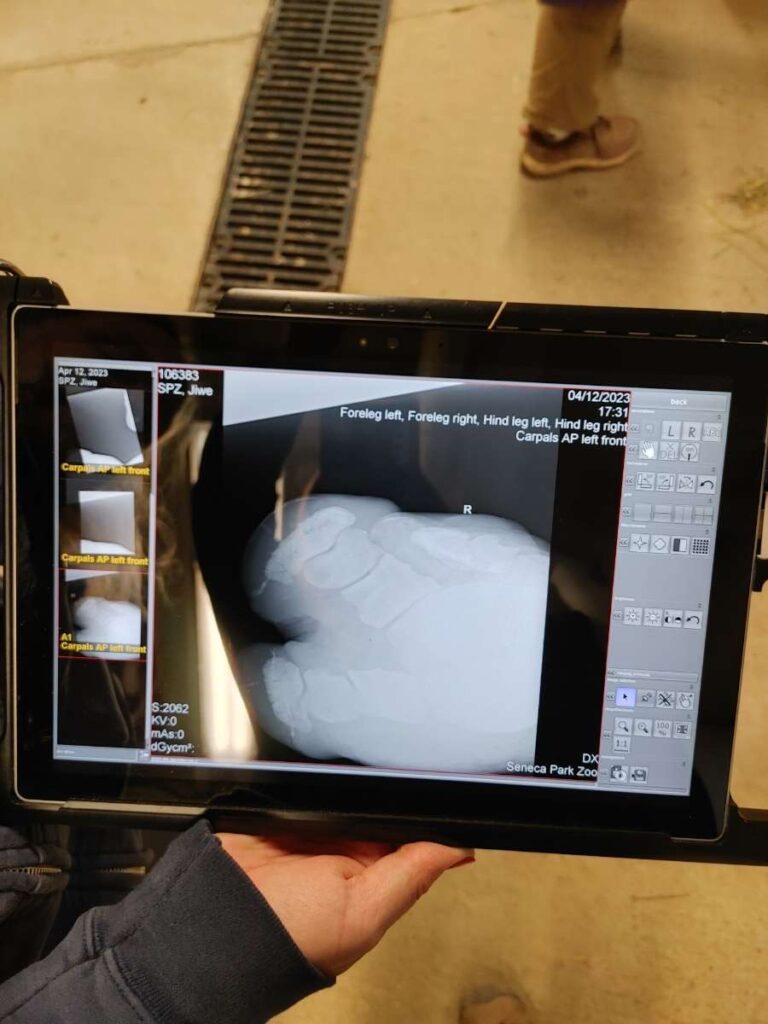

The work of our Animal Care and Animal Health teams extends far beyond what a guest sees or hears on the news. Many of these efforts are classified as “Science Saving Species”. Through collaboration with universities, state and federal agencies, nonprofits, and other zoos Seneca Park Zoo advances the understanding of biology, physiology, and well-being in a variety of species. One key example is assisted reproduction, where Seneca Park Zoo actively works with the scientists at CREW (Center for Conservation Research of Endangered Wildlife) contributing to the science and the species, of lynx, polar bear, and African lions.

The Zoo is actively involved in scientific studies and research that span the activities and species here. In 2023, the Zoo collaborated with scientists at Carnegie Mellon, George Mason University, the University of Rochester, RIT, St. John Fisher, University of Iowa, University of Missouri, University of Oxford, as well as Binder Park Zoo, CREW and New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Research included red pandas, African penguins, bats, polar bears, North American river otters, African lions, snakes, giraffe, snow leopards, and the many species that share habitat with us in Monroe County.

Pillar Four: Participate in Regional Conservation Efforts

Seneca Park Zoo has been actively involved in species survival in our own backyard for decades. Not only is our own region the place where we can make the most impact, but it’s essential that our community understand that conservation isn’t something that needs to happen just in Africa or Borneo or Nepal, but that our region faces significant challenges we can all be involved in addressing.

Regionally, our anchor species have been lake sturgeon, North American river otters, Eastern Massassagua Rattlesnakes, and monarch butterflies

Lake Sturgeon

Twenty years of collaboration between the United States Geological Survey (USGS), New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC), United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) and Seneca Park Zoo underscores how conservation partners and a community bring an indigenous species back from the brink of extinction.

North American River Otter

More than twenty years ago, the Zoo participated in relocating North American river otters to the region, as they had been extirpated. Today, general Curator David Hamilton works with partners at RIT to study the presence and genetics of regional otters.

Eastern Massassauga Rattlesnake

The Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake Species Survival Plan (SSP) surveys wetlands looking for rattlesnakes. Each rattlesnake found is weighed, measured and a blood sample is collected.

Monarch Butterfly

Seneca Park Zoo has been conserving pollinator sites since 2002 with our Butterfly Beltway programs. Over 120 acres of native plants specifically chosen to feed and support monarchs and native wildlife have been planted.

We also are a part of the Urban Wildlife Information Network, documenting and reporting on the species sharing habitat with us in Monroe County. We work in partnership with governmental, nonprofit, and academic partners to achieve our work, and we often invite the public to be part of our efforts.

In recent years, the Zoo accelerated its coordination of Community Clean Ups, which now take place at least monthly from March through October. In 2023, nearly 700 volunteers joined us, contributing some 1800 hours of time to remove debris from our beaches, parks, and waterways. In the past five years, Community Clean Ups have removed over 13,000 pounds of pollution.

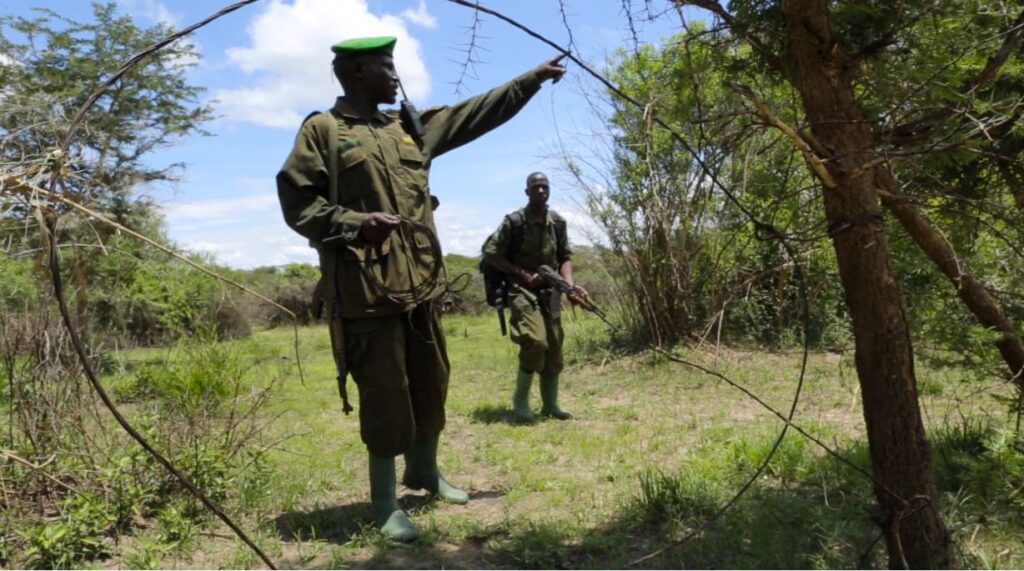

Pillar Five: Create meaningful partnerships for global conservation actions

The focus of this pillar is on the word “meaningful”. We hope you’ve noticed the many times the lead article in ZooNooz is written by a colleague from one of our conservation partners, sharing the work they can accomplish because of support from our members, guests, and donors. We consider our grantees our partners in achieving our shared mission.

Here are just a few examples:

Lemurs and Madagascar

Our partnership with Dr. Patricia Wright remains steadfast, supporting reforestation and key biodiversity assessments in Madagascar. As was reported in a recent ZooNooz, staff travels to Madagascar on a regular cadence in addition to our providing financial support.

Panamanian golden frogs

Our partnership with El Valle, in Panama, saw Curator John Adamski and Zookeeper Catina Wright travel earlier this year to assist with husbandry of Panamanian golden frogs as well as strategy for that species’ survival moving forward.

Polar Bears

Seneca Park Zoo, through its multi-year partnership with the Rochester Americans for Defend the Ice, has been able to significantly increase public awareness of the shrinking sea ice upon which polar bears depend. It’s also allowed us to increase our financial support for the maternal den monitoring research at Polar Bears International (PBI).

In 2023, we were also able to send Zookeeper Heidi Beifus to Churchill as part of PBI’s Arctic Ambassador program. In addition, we have been working closely with PBI and other zoos with polar bears to replicate the Defend the Ice program in other hockey markets.

"This is a small glimpse into our conservation work and it is at the heart of WHY we do what we do. We are so proud of the work we accomplish together, with your help."

- Pamela Reed Sanchez, President and CEO Seneca Park Zoo Society