Every year, Seneca Park Zoo Society raises thousands of dollars for conservation efforts locally and globally. And while our conservation partners need financial assistance, they also need help we can only provide by sending staff members to their sites. In 2019, funds were made available to send Zoo Keeper Kevin Blakely to SANCCOB in South Africa where he spent two weeks in December helping to rehabilitate African penguins.

A zoo keeper at Seneca Park Zoo since 2013, Kevin is the primary African penguin keeper and has long been interested in marine animals.

“My passion for marine animals began when I was at college and living in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. I went on snorkeling trips to the Florida Keys and visited the Ft. Lauderdale aquarium regularly. I had my first saltwater aquarium in my college apartment, and I’ve had at least one in my home ever since!”

“Donations and money are great and always needed, but organizations like SANCCOB really do appreciate people on the ground. SANCCOB welcomes volunteers of all experience levels and backgrounds because there’s always something that needs to be done, from laundry and cleaning to food prep.”

Following an extensive application process and a nearly 18-hour flight, Kevin made it to SANCCOB’s main facility in Table View, South Africa. Each morning began with an all-staff meeting to review pen assignments, supervisor roles, and any symptoms to look for in the penguins.

On Kevin’s first day, he was assigned to food prep, which is the heart of SANCCOB’s operations. He spent the entire day learning the food prep area, which includes medications and vitamins, and how to clean syringes and prepare formula for the penguins.

“Most volunteers are only around for a couple of weeks, so they need you up to speed and working from day two. The first couple of days can be hectic and overwhelming as you learn their procedures.”

Within a couple of days, Kevin was inside a pen feeding penguins. He picked up procedures quickly thanks to his experience with the Zoo’s African penguin colony, and it wasn’t long before Kevin was named a pen supervisor.

“I love to learn new things and be challenged. One of my proudest moments was coming in one morning to see my name listed as a pen supervisor. To start out and have no idea what’s going on, I was proud of how quickly I became comfortable with my assignments.”

“One-hour swimmers”

Seabirds administered to SANCCOB are divided into pens based on swimming abilities. Kevin was responsible for Pen 5, which at one point held 42 penguins. With 12 pens in total, two to three people are needed in each pen and birds are consolidated based on amount of help available. Pen 5 was home to many “one-hour swimmers”, which refers to the length of time a bird can swim during a session. When penguins are close to release, they need to be able to swim at least one-hour straight three times a day.

Kevin aimed to get the penguins into the water first thing in the morning so they could swim for one of their three hours. During that time, he would clean their pen, mats, walls, and equipment. After the first swim, it was time to prepare for feeding.

Each penguin gets three large fish (120-130 fish are prepped daily!) and formula – a blend of seafood, vitamins, and minerals. Some of the penguins also need electrolytes, additional medications, and to use the nebulizer to aid in their respiratory issues.

The SANCCOB facility has two pools about two-feet deep, with six pens surrounding each pool. After each swim, the penguins’ feathers are examined to ensure they’ve retained their waterproofing and their weight is checked for respiratory issues. The goal is to get them in the ocean as soon as possible.

“One of the most rewarding parts of volunteering at SANCCOB was realizing how much I was needed. Our work was important. It wasn’t just a vacation. Sometimes I was working 10-hour days, but I didn’t want to leave.”

Adopting a penguin

While supervising Pen 5, Kevin connected with an adult penguin that had come to the center three months earlier emaciated and suffering from a bad foot injury. Once the penguin was stabilized, it was determined that removing the injured foot was his best chance for survival. After months of rehabilitation, the penguin was finally cleared for release and Kevin had the opportunity to be a part of it.

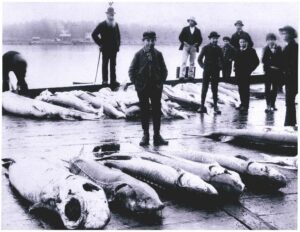

To honor this bird’s fighting spirit and to thank SANCCOB for their tireless efforts to save seabirds, Kevin adopted the bird on behalf of Seneca Park Zoo and named him SPeeZy. On December 23, 2019, Speezy was released at the site of the Stony Point penguin colony, along with 16 other African penguins.

Seabirds that have been deemed non-releasable permanently live at SANCCOB in their “Home Pen”, while the ICU Pen is for “10-minute swimmers”. Because many pens are at capacity, SANCCOB’s work to rehabilitate disabled penguins for release, like Speezy, is so critical.

“Traveling to South Africa and working at SANCCOB was a dream come true. When you work with an endangered animal daily, it becomes very personal. During all my keeper chats at the Zoo, I not only try to educate our guests about the threats faced by African penguins, but also how people can help from right here in Rochester. For me to be able to go there and be part of the SANCCOB team, even for a short time, was an incredible honor and something I hope to do again very soon.”

The Dilemma: The Clutch and Molt Overlap

About 90% of the birds at SANCCOB are “blues,” or between juveniles and chicks. At this age, they’ve molted out of their feathers but can’t feed themselves and are still with their parents.

Normally, African penguins breed in the autumn and winter – between March and September. By October and November, the last chicks would have fledged and adults begin spending several weeks at sea fattening up for molt, which happens in November and December. In recent years, breeding has been delayed and the birds run into a dilemma late in the year.

When the penguins lay eggs in March or April, there are often heat waves and extreme storms in South Africa, which causes the birds to abandon their eggs or lose their clutches altogether (penguins usually lay two eggs per clutch).

The main reason for this delayed breeding is the decline of sardine and anchovy populations, the African penguin’s main prey, due to overfishing and climate change. Because of this, penguins are struggling to find enough food to be fit enough for breeding season.

Food availability, as well as environmental changes, has shifted breeding to later in the year when conditions improve. Many penguins now successfully lay eggs and start raising chicks in late winter (August/September or later). Therefore, these chicks are still in the need of parental feeding when the parents are due to molt.

African penguins fully shed their feathers once a year to secure waterproofing. Molting requires them to stay on land for several weeks, so they can’t hunt for themselves or their chicks during that time. Unfortunately, many penguins go into molt and are left standing next to their chicks at the nest site but unable to feed the them.

That’s where SANCCOB’s Penguin Rangers come in. Abandoned and weak chicks are identified and removed from the colony and taken to SANCCOB for hand-rearing and later, release back into nature. SANCCOB is working closely with the South African government and the managing authorities to try and address these problems and secure safe breeding spaces for the birds.

It is estimated there are only around 13,200 breeding pairs left in all South Africa.

– Zoo Keeper Kevin Blakely

Ways you can help African penguins:

- Adopt a penguin at SANCCOB – Adopt an African penguin or penguin egg that will be rehabilitated and released or adopt a ‘Home Pen’ bird that lives permanently at SANCCOB. Funds help to provide incubation, food, and veterinary treatment.

- Donate to SANCCOB – Whether you donate your time or money, you can make a difference in the survival of endangered African penguins and other seabirds in distress. For more information, visit sancob.co.za.

- Visit the Zoo to learn more about African penguins and the threats they face in nature through keeper chats, special experiences, and more.

- Purchase sustainably sourced seafood – Purchase seafood caught or farmed in ways that support a healthy ocean. Ask your local grocer if they sell sustainable seafood and visit seafoodwatch.org to learn more about eco-friendly options.